The roots of rock lie deep in the soil of voodoo. With today's post I dig them up with the help of Michael Ventura. Ventura is a sometime author, essayist, film critic, and poet who currently writes for the "Austin Chronicle." Now seventy years of age, he has spent decades observing and commenting on the more intellectual aspects of American culture. In 1986 he published a collection of eleven essays under the title Shadow Dancing in the USA. It is still in print. One of those essays, "Hear That Long Snake Moan", was an historical criticism of the roots of rock music. It exists online as a standalone 32 page pdf that has been cited in the equivalent of peer reviewed papers as of this writing twenty eight times. Today's blog post is essentially my summation of that essay with extensive quotations.

The roots of rock lie deep in the soil of voodoo. With today's post I dig them up with the help of Michael Ventura. Ventura is a sometime author, essayist, film critic, and poet who currently writes for the "Austin Chronicle." Now seventy years of age, he has spent decades observing and commenting on the more intellectual aspects of American culture. In 1986 he published a collection of eleven essays under the title Shadow Dancing in the USA. It is still in print. One of those essays, "Hear That Long Snake Moan", was an historical criticism of the roots of rock music. It exists online as a standalone 32 page pdf that has been cited in the equivalent of peer reviewed papers as of this writing twenty eight times. Today's blog post is essentially my summation of that essay with extensive quotations. Rock music is historically and undeniably rooted in West African and Haitian voodoo traditions. We see this illustrated linguistically via such words as "funky", "mojo", "boogie", and "juke." All of these, and others, come from the West African language of Ki-Kongo, and in their original language mean respectively positive sweat, soul, devilishly good, and bad.

Along the West African coast even well into the nineteenth century an old culture thrived loosely labeled as Yoruba. Like ancient India, China, Egypt, and Ireland it embraced a pagan mother goddess religion, and its worship rites were intimately connected with drum induced bodily trances through which the gods communicate to men.

To meditate was to dance. Hence in this culture the drum is so sacred as an instrument that some are built for display. They are too holy to touch. “An instrument of significant silence, not reverberation,” is Thompson’s phrase. It’s as though such a drum is there to say that within the astonishingly complex rhythms of Africa – rhythms which Western musical notation is too crude, rhythmically, to express – within the multi-toned din is a core of quietude, of calm, the focused silence of the Master, the silence out of which revelation rises.

It is Ventura's contention (and many others I have read) that civilized Europe produced a music – classical – that was designed to appeal primarily not to the body but to the mind. He credits this essentially to the influence of Christianity which downplays the body. Africa, on the other hand, in its core, held a different musical philosophy because it held a different religious philosophy. West Africa views the spirit world as existing alongside the human world and that they periodically intersect.

Their sign for this is the cross, but it has nothing to do with the Christianist cross... The metaphysical

goal of the African way is to experience the intense meeting of both worlds at the crossroads. Writes Thompson, “Ritual contact with divinity underscores the religious aspirations of the Yoruba. To become possessed by the spirit of the Yoruba deity, which is a formal goal of the religion, is to ‘make the god,’ to capture numinous flowing force within one’s body.”

goal of the African way is to experience the intense meeting of both worlds at the crossroads. Writes Thompson, “Ritual contact with divinity underscores the religious aspirations of the Yoruba. To become possessed by the spirit of the Yoruba deity, which is a formal goal of the religion, is to ‘make the god,’ to capture numinous flowing force within one’s body.” The route to accomplish this meeting of the worlds at the intersection of the cross is – you guessed it – drumming.

Spurred by the holy drums, deep in the meditation of the dance, one is literally entered by a god or a goddess. Goddesses may enter men, and gods may enter women. Westerners call this “possession.”

Maya Deren, a mid-twentieth century avante-garde documentarian, spent extensive time in Haiti producing films which document these ancient practices. I have spent hours poring over them on YouTube. A collection of her shorts is available for sale on Amazon and she is there labeled as the "mother of trance film."

I realize Haiti is not West Africa but the racial and religious connections between the two are factually undeniable. They are illustrated with one word: slavery. It was slavery that brought West Africans along with their religion by the tens of thousands to Haiti. And it is in Haiti that Deren saw seventy years ago and can still be seen today the practice of this West African religion.

In Abomey, Africa, these deities that speak through humans are called vodun. The word means “mysteries.” From their vodun comes our “Voodoo.” And it is to Voodoo that we must look for the roots of our music.

Even when a bastardized Caribbean Roman Catholicism sought to absorb voodoo within its own iconography the West African heritage won out. Ventura explains the goal and process of voodoo this way:

The hungan may be healer, personal adviser, and political broker, but his – or, for a mambo, hers, for women are as numerous and powerful as men in this religion – most important function is to organize and preside over the ceremonies in which the loa, the gods, “ride” the body of the worshiper. The ecstasy and morality of vodun intersect in this phenomenon. The god is seen as the rider, the person is seen as the horse, and they come together in the dance…

“There’s a whole language of possession,” Thompson writes, “a different expression and stance for each god.” All the accounts are clear that a god is instantly recognized by its movements, and the movements are different for each. So if the ceremony is to honor Ghede, their equivalent of Hermes, perhaps Erzulie, their Aphrodite, shows up uninvited. But she is recognizable whether she rides a man or a woman because of her distinctive movements and behavior. … here are people who can dance it! Here are people who can, to use Jungian terminology, embody an archetype – any single Voodoo worshiper may embody many during a lifetime of ceremonies. They will dance it, speak it, make love through it, manifest it in every possible way, entering and leaving the experience without psychosis, without “mind-expanding” drugs, and while having the support and help of their community, for all of this is integral with their daily lives.

They do all of this via the voodoo ceremonies driven predominantly by rhythm and its near kinsman, dance.

In Haitian Voodoo, as in Africa, the drum is holy. The drummer is seen merely as the servant of the drum – he has no influence within the hierarchy of the religion, but through his drum he has great influence on the ceremony. Each loa prefers a fundamentally different rhythm, and the drummer knows them all and all their variations. He can often invoke possession by what he plays, though a drummer would never play a rhythm that would go contrary to the ceremony’s structure as set by the hungan or mambo.

In Haitian Voodoo, as in Africa, the drum is holy. The drummer is seen merely as the servant of the drum – he has no influence within the hierarchy of the religion, but through his drum he has great influence on the ceremony. Each loa prefers a fundamentally different rhythm, and the drummer knows them all and all their variations. He can often invoke possession by what he plays, though a drummer would never play a rhythm that would go contrary to the ceremony’s structure as set by the hungan or mambo. Ventura goes on to connect the Haitian voodoo not only to its primary West African Yoruba roots, but also to the Irish druidic pagan culture and the kabbalah. As a decently educated student of world history and religion when placed alongside a scriptural perspective I have zero problem seeing the demonic similarities and connections in all of these.

In such a way, via slavery, paganism, ritual sacrifice, possession, rhythm, and dance the West African/Haitian religion of voodoo entered the American stream through the jazz of New Orleans.

Jazz and rock’n’roll would evolve from Voodoo, carrying within them a metaphysical antidote for both the ravages of the mind-body split codified by Christianism and the onset of technology. The twentieth century would dance as no other had, and, through that dance, secrets would be passed. First North America, and then the whole world, would – like the old blues says – “hear that long snake moan.”

By the early 1800's New Orleans was the center of the free black culture in the United States. Constant warfare on Haiti had sent streams of black people north to relative safety. Long a Roman Catholic stronghold as well, the Catholic voodoo mixture of these refugees found a home in Louisiana. A Haitian saying goes, "If you want the loa to leave you alone become a Protestant." Catholicism, on the other hand, was never interpreted as an attack on the West African nativist religions. Robert Tallant, author of the 1946 book Voodoo in New Orleans, which is still in print, asserts that voodoo began as a semi-organized system there by 1803.

It was in this spiritually toxic swamp that jazz was born. New Orleans' Congo Square in the mid-nineteenth century played host to massive black musical celebrations. An 1853 eye witness account from Henry Edward Durrell well shows the descended affinity the new born jazz would have with Haitian voodoo and its older mother, the West African Yoruba paganism:

Upon entering the square, the visitor finds the multitude packed in groups of close, narrow circles, of a central area of only a few feet; and there in the center of each circle sits the musician, astride a barrel, strong-headed, which he beats with two sticks, to a strange measure incessantly, like mad, for hours together, while the perspiration literally rolls in streams and wets the ground; and there, labor the dancers male and female, under an inspiration of possession, which takes from their limbs all sense of weariness, and gives to them a rapidity and a duration of motion that will hardly be found elsewhere outside of mere machinery. The head rests upon the breast, or is thrown back upon the shoulders, the eyes closed, or glaring, while the arms, amid cries, and shouts, and sharp ejaculations, float upon the air, or keep time, with the hands patting the thighs, to a music which is seemingly eternal.

In this environment – populated by the prostitutes of Storyville, the voodoo queens of the late nineteenth century, and the West African Yoruba drumming and dancing – jazz was born. Jelly Roll Morton's – the first man to publish a jazz composition in 1915 - mother was a Storyville madam. Buddy Bolden, perhaps the first recognized great jazz musician, played New Orleans from 1895-1907 until going insane at the tender age of thirty.

Incrementally, ragtime became jazz, jazz developed into the blues, the blues picked up the West African rhythms to become rhythm and blues, and the harder, wilder R and B singers became the first rock stars. Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, and Janis Joplin all grew up in the Deep South, a musical culture heavily influenced by New Orleans.

From the first, jazz borrowed the concept of trance that had originated all the way back in West Africa. Harnett Kane wrote in 1949 of Buddy Bolden that "his ability of playing had one indispensable feature, 'the trance.' " Cecil Taylor, a still living jazz legend, describes it this way: "Most people don't have any idea what improvisation is… It means the magical lifting of one's spirits to a state of trance… It means experiencing oneself as another kind of living organism, much in the way of a plant, a tree – the growth, you see, that's what it is… it's not what do with 'energy.' It has to do with religious forces." He went on to say, "Part of what this music is about is not to be delineated exactly. It's about magic, capturing spirits."

Ventura says:

The overt practice of Voodoo faded at the very moment the music was born, as though it had done its job here. Voodoo imagery would live in the lyrics and song titles through all the music’s forms – jazz, blues, rhythm and blues, rock’n’roll and even some gospel – until the present, and many of the mojos sung about were real indeed.

Voodoo and its associations, particularly in the form of the snake, can be found all over the Southern music of the first half of the twentieth century.

“I got a great long snake crawling around my room” is something Blind Lemon Jefferson, the first great rural blues singer to record, would sing in the 1920s; Joe Ely would rock the same line in the 1980s, and

in both cases the image would overpower the song and the singers would have to wail a mystery that included sex but was more than sex. Willie Dixon would write Voodoo lyrics that Muddy Waters would make famous; the old blues singer, Victoria Spivey, when she formed her own small record label in the 1960s, would use her logo a woman dancing with a snake. In the late 1970s Irma Thomas, the New Orleans singer, would record a tune called “Princess Lala” – based on Lala, a famous Voodoo queen in the New Orleans of the 1930s and 1940s – with a fairly accurate Voodoo practice described in the lyric. And there would be Voodoo rumors all along: that Buddy Bolden’s eventual insanity was a hex (though a man through whom so much numinous force was pouring might well break under the pressure after a few years); that Robert Johnson, the great blues player of the 1930s whose style and rhythms were a direct source for rock’n’roll, sold his soul to the Devil to play and sing like he did, and that he was done in by Voodoo; and the mourners at Jelly Roll Morton’s funeral would say that his godmother, Eulalie Echo, a queen of Storyville, had sold his soul for her power when she was young and ruined his chance for happiness (though he had plenty of soul to play with – nobody ever played with more – for forty years). These are serious people saying these things, and it would be unwise to discount them out of hand.

in both cases the image would overpower the song and the singers would have to wail a mystery that included sex but was more than sex. Willie Dixon would write Voodoo lyrics that Muddy Waters would make famous; the old blues singer, Victoria Spivey, when she formed her own small record label in the 1960s, would use her logo a woman dancing with a snake. In the late 1970s Irma Thomas, the New Orleans singer, would record a tune called “Princess Lala” – based on Lala, a famous Voodoo queen in the New Orleans of the 1930s and 1940s – with a fairly accurate Voodoo practice described in the lyric. And there would be Voodoo rumors all along: that Buddy Bolden’s eventual insanity was a hex (though a man through whom so much numinous force was pouring might well break under the pressure after a few years); that Robert Johnson, the great blues player of the 1930s whose style and rhythms were a direct source for rock’n’roll, sold his soul to the Devil to play and sing like he did, and that he was done in by Voodoo; and the mourners at Jelly Roll Morton’s funeral would say that his godmother, Eulalie Echo, a queen of Storyville, had sold his soul for her power when she was young and ruined his chance for happiness (though he had plenty of soul to play with – nobody ever played with more – for forty years). These are serious people saying these things, and it would be unwise to discount them out of hand. Let us pause for a moment and compare this increasingly rhythm dominated music with traditional Western music. Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven move us emotionally (music is an emotional language, remember?) but rarely physically. Even the dancing done to traditional Western music constrains the body into a fairly upright posture with only the feet moving. Ragtime and jazz, rhythm and blues held no such compunctions, and when New Orleans' Storyville was closed in 1923 that music exploded out of New Orleans into juke joints all over the South. Indeed, it even went north to Chicago.

By 1930, African rhythm – not African beats, but European beats transformed by the African – had entered American life to stay. Which is to say, the technical language and the technique of African metaphysics was a language we were all beginning, wordlessly, to know. America was excited by it. America was moving to it. America was resisting it. American intellectuals were pooh-poohing it. But the dialectic had been joined.

This music, increasingly recorded and available on disc, a music soaked in sex, dance, and trance, became the father of the "race records" of early rock and roll.

When white intellectuals started to discover rural blues in significant numbers, in the late fifties and early sixties, they were discovering it out of context; for them, on records or in “folk music” settings it was strictly a music to be listened to. In the joints where it was played in its heyday, it was a dancing music. Sometimes it was a piano, sometimes a combination of instruments, and often just one man with a guitar, but people came to mingle, to gamble, and to dance. The relationship of musician to dancer was exactly the same as the relation of drummer to dancer in Haitian Voodoo, where a drummer worked closely with the dance and could often evoke possession at will. Texas barrelhouse piano player Robert Shaw put it this way much later: “When you listen to what I’m playing, you got to see in your mind all them gals out there swinging their butts and getting the mens excited. Otherwise you ain’t got this music rightly understood. I could sit there and throw my hands down and make them gals do anything. I told them when to shake it and when to hold it back. That’s what this music is for.”

…Arthur “Big Boy” Cruddup was the first to accompany his singing on electric guitar for a record, in 1942. Over the next several years he made very popular “race” records, doing electrically the rhythms and feels that Robert Johnson had recorded acoustically in 1936. (In 1954, Elvis Presley’s first recordings would be Big Boy Cruddup numbers, often imitating Cruddup’s delivery note-for-note.) Sonny Boy Williamson, Professor Longhair, Pete Johnson, Big Joe Turner, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Little Walter, and Cliften Chenier, among others, would by the late forties have created the lineup that would be a rock’n’roll band: electric guitar, drums, bass, harmonica and/or saxophone, and occasionally a piano. Those men made a wild, haunting music – the long snake moaning plain. Theirs was the music, in those little sweaty juke joints, that Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins, among others, sneaked off to hear when they hit their teens in the late forties. These and the others who would first play what came to be known as rock’n’roll were claimed by this music, this insistence by the dance itself that it survive.

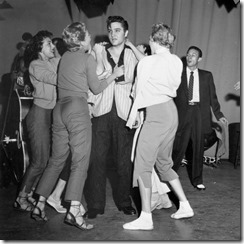

Elvis Presley took the American world by storm. Singing black music with black vocals and shaking his hips the way he had learned in those black juke joints he threw his entire body and soul into the music. He played and sang with an abandon shocking for his day and time. And it changed everything.

Elvis before the Army, before 1959, was something extraordinary: a white man who seemed, to the rest of us, to appear out of nowhere with moves that most white people had never imagined, let alone seen. His legs weren’t solidly planted then, as they would be years later. They were always in motion. Often he’d rise on his toes, seem on the verge of some impossible groin-propelled leap, then twist, shimmy,

dip, and shake in some direction you wouldn’t have expected. You never expected it. Every inflection of voice was matched, accented, harmonized, by an inflection of muscle. As though the voice couldn’t sing unless the body moved. It was so palpably a unit that it came across on his recordings. Presley’s moves were body-shouts, and the way our ears heard his voice our bodies heard his body. Girls instantly understood it and went nuts screaming for more. Boys instantly understood it and started dancing by themselves in front of their mirrors in imitation of him. Nobody had ever seen a white boy move like that. He was a flesh-and-blood rent in white reality. A gash in the nature of Western things. Through him, or through his image, a whole culture started to pass from its most strictured, fearful years to our unpredictably fermentive age – a jangled, discordant feeling, at once ultramodern and primitive, modes which have blended to become the mood of our time.

dip, and shake in some direction you wouldn’t have expected. You never expected it. Every inflection of voice was matched, accented, harmonized, by an inflection of muscle. As though the voice couldn’t sing unless the body moved. It was so palpably a unit that it came across on his recordings. Presley’s moves were body-shouts, and the way our ears heard his voice our bodies heard his body. Girls instantly understood it and went nuts screaming for more. Boys instantly understood it and started dancing by themselves in front of their mirrors in imitation of him. Nobody had ever seen a white boy move like that. He was a flesh-and-blood rent in white reality. A gash in the nature of Western things. Through him, or through his image, a whole culture started to pass from its most strictured, fearful years to our unpredictably fermentive age – a jangled, discordant feeling, at once ultramodern and primitive, modes which have blended to become the mood of our time. Within months of his tremendous radio successes came Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Chuck Berry singing and playing the music they had known most of their life. I cannot help but say it again – everything had changed.

It is important to recognize that when whites started playing rock’n’roll, the whole aesthetic of Western performance changed. Wrote Alfred Metraux of Haitian Voodoo dancing: “Spurred by the god within him, the devotee… throws himself into a series of brilliant improvisations and shows a suppleness, a grace and imagination which often did not seem possible. The audience is not taken in: it is to the loa and not the loa’s servant that their admiration goes out.”

In American culture we’ve mistaken the loa’s servant for the loa, the horse for the rider, but only on the surface. We may have worshiped the horse, the singer-dancer, but we did so because we felt the presence of the rider, the spirit. John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful said it succinctly in one of his lyrics:

And we’ll go dancin’

And then you’ll see

That the magic’s in the music

And the music’s in me

Knowingly or unknowingly the door to the occult had swung open wide on an entire but as yet unsuspecting American culture.

The Voodoo rite of possession by the god became the standard of American performance in rock’n’roll. Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, James Brown, Janis Joplin, Tina Turner, Jim Morrison, Johnny Rotten, Prince – they let themselves be possessed not by any god they could name but by the spirit they felt in the music. Their behavior in this possession was something Western society had never before tolerated. And the way a possessed devotee in a Voodoo ceremony often will transmit his state of possession to someone else merely by touching the hand, they transmitted their possession through their voice and their dance to their audience, even through their records.

Dominated by rhythm and revealed by dance, the pagan West African Yoruban mother goddess religion had begun to win the battle for the minds and bodies of the American teenager.

“Let your backbone slip,” is how many lyrics put it. Or, as Jerry Lee Lewis instructed in the spoken riff of his classic “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On”: Easy now… shake… ah, shake it baby… yeah… you can shake it one time for me… I said come on over, whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on… now let’s get real low one time… all you gotta do is kinda stand… stand in one spot… wriggle around, just a little bit… that’s what you got… whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on…

It’s not only that he’s described the dance that George W. Cable and others described in Congo Square; it’s that, as Lewis says, “we ain’t fakin’.” The measure of how much we ain’t fakin’ is that you can see in Maya Deren’s 1949 footage of Haitian Voodoo dancers exactly the same dancing that you’ve seen from 1959 to the present wherever Americans (and now Europeans) dance to rock’n’roll.

Duke Ellington put it this way in his immortal ode to the drum, "A Drum Is a Woman" (by which he meant a goddess):

Rhythm came from Africa to America.

Do you know what it does to you?

Exactly what it's supposed to do.

When Elvis introduced America to rock and roll, there were a lot of Biblical Christians who were stunned and frightened by it at the time. Some used it as a way to shame and marginalize blacks. Others spoke out against it calling it voodoo music and the Devil’s music. Many in the church chose to ban dancing from that point on and would not allow their teenage sons and daughters to attend proms.

ReplyDeleteThe world laughed at them, mocked them and made fun of them because they felt the church was denying them their fun.

My question for you Pastor is: Do you think Christians of the 50s responded properly back then? If so, why? If not, what should they have done differently?

That's an interesting question, and one I would answer both yes and no. Their instinctual reaction that this music was demonic was correct. The problem - amongst others - is that they did not so much react logically and explain this to young people as react emotionally. In so doing their emotionalism against rock became just as much if not more an expression of their racism. This became about nigger music (pardon the term please), promoted by nigger lovers, and a danger to our lily white youth.

Delete...which is appalling on several different levels. Fundamentalism has long struggled with racism. My next book will speak to this in some detail.

When we (Christianity) make ethnicity/race the issue we will always lose in the long term. And rightly so. Yes, this music was "black" music but that was b/c their heritage was African and they were dragged here as slaves. The problem is not the black roots of rock music; it is the demonic roots that are the issue.

Thank you Pastor Brennan for this excellent thoughtful study. The change in music and the subsequent accompanying "casual" attitude in worship in my own church is grieving my heart deeply. What I am reading here has provided numerous "ah ha" moments. "Now I understand". Now I understand why my spirit is so troubled. Though subjectively I've known something is dangerous, you have provide objective reasons for my concern.

ReplyDeleteThis now causes me to question even more fervently, "Why aren't others who are good brothers/sisters equally troubled."

You ask, "Why aren't others who are good brothers/sisters equally troubled?"

ReplyDelete...b/c they don't want to be. It would force them into a complete paradigm shift in both their concept of worship and their private lives. These are highly uncomfortable facts. It is so much easier to ignore their existence.

Most of what we believe about hell comes from Catholicism and is incorrect. I should clarify here that I do not mean to say that Augustine invented the concept of hell. I meant to say that Augustine invented the concept of hell as eternal punishment.

ReplyDeleteThe concept of ‘eternal punishment in hell' is a doctrine embraced and christianised by the Roman Catholic Church in the early centuries of Christianity, and made official when Jerome translated the Bible into Latin in 400 A.D.

Jerome mistranslated and misinterpreted several key Hebrew and Greek words into the Latin Vulgate in support of the already established doctrine of hell of the Roman Catholic Church. The Latin Vulgate, as translated by Jerome, had such an overpowering dominance for over a thousand years that many subsequent Bible versions, especially the King James Version (KJV), have simply carried forward the translation and interpretation errors to varying degrees in support of the doctrine of hell.

The doctrine of everlasting punishment in hell is founded upon a combination of mistranslations and misinterpretations of the following Hebrew and Greek words.

Mistranslations of the Hebrew word sheol and the Greek words hades, tartarus and gehenna, to mean hell.

Mistranslations of the time-related Hebrew word owlam and the time-related Greek words aionand aionios, to mean everlasting when relating to God’s future punishment of unbelievers.

In the third century, Origen of Alexandria formulated a teaching he termed apokatastasis(restoration). According to this doctrine, all sinners—and indeed all of the fallen angels, including Satan himself—would be, through Christ’s grace, brought to salvation in the end. There might be hellfire, Origen thought, but it cannot be everlasting, for if it were, sin would prove more powerful than grace. Well, the official church reacted against Origen’s universalism, for she saw it as insufficiently respectful of freedom, both human and angelic. If God’s grace is simply irresistible, then the real freedom to reject God’s love appears compromised.

In the wake of this condemnation, other theologians moved practically to the other extreme. St. Augustine, fifth century bishop of Hippo, held that original sin had produced amassa damnata (a damned mass) of human beings, out of which God, in his inscrutable grace, has deigned to pick a few privileged souls. Thus, Augustine clearly believed that the vast majority of the human race would be damned to hell. St. Thomas Aquinas followed Augustine in holding that a very large number of people are Hell-bound; he even taught that among the pleasures that the saints in heaven enjoy is the contemplation of the suffering of the damned.

I understand your comment, though I disagree with it. What I don't understand is how this relates to the blog post.

DeleteHello Pastor, I came across this post after reading the paper, some five years after you wrote this. I agree with a lot of what you say here about the paper and the spiritual issues addressed therein. Our only disagreement on this subject seems to be whether or not music-induced ecstatic trance is "good" or "bad." We agree, however, that this phenomenon is real.

ReplyDeleteWhat are your feelings or thoughts on the statement in the paper (p. 10) that Protestantism is where we "...have the mind-body split at its most virulent...?" I am not a Christian, but I am not asking this as an oblique attack on your faith or beliefs; I am genuinely curious as to your perspective, and whether or not you feel that this statement is a mischaracterization.

I don't think it is a mischaracterization as much as an ill-informed opinion. It is only loosely accurate. Protestantism is a not monolithic, though it often does share more of an allegiance to and promotion of the Bible than, say, Roman Catholicism does. To that extent, there is what I think to be a biblically based influence that downplays the body. Paul in Romans 8 uses the word mortify, not in a literal sense, but in a real sense and tells us to mortify the flesh. The more biblical a religious tradition the more it will seek to control or minimize the appetites of the body and elevate those of the mind.

Delete